Note: This site is moving to KnowledgeJump.com. Please reset your bookmark.

ADDIE Model

ADDIE (Analysis, Design, Development, Implement, and Evaluate) is a model of the ISD family (Instructional System Design). It has evolved several times over the years to become iterative, dynamic, and user friendly. ISD includes other models, such as the Dick and Carey (2004) and Kemp (Gustafson, Branch, 1997) models.

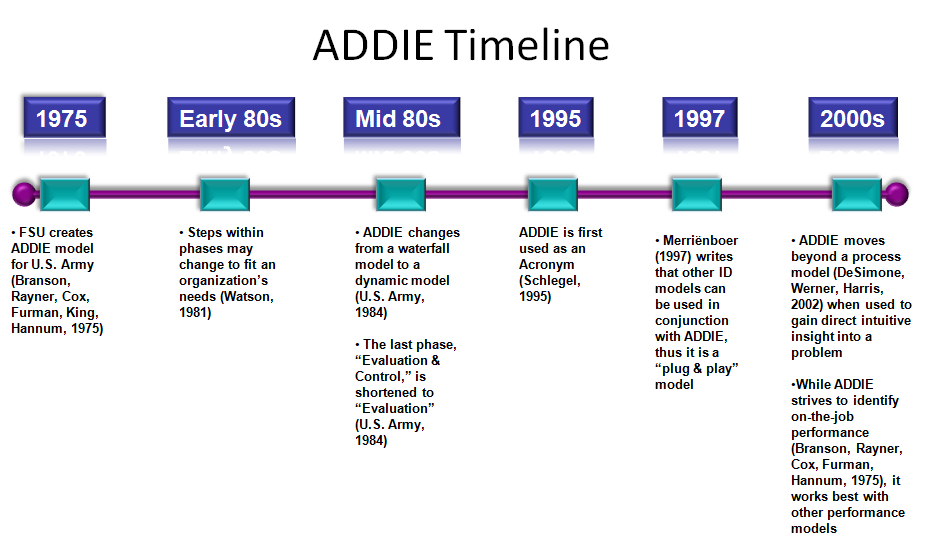

While the concept of ISD has been around since the early 1950s, ADDIE first appeared in 1975. It was created by the Center for Educational Technology at Florida State University for the U.S. Army and then quickly adapted by all the U.S. Armed Forces (Branson, Rayner, Cox, Furman, King, Hannum, 1975; Watson, 1981). The five phases were based somewhat on a previous ISD model developed by the U.S. Air Force (1970) called the Five Step Approach. It also has a lot in common with Bela Banathy's model.

As defense machinery was becoming more and more sophisticated, the educational background of entry level soldiers was becoming lower and lower. The potential solution to this problem was in the form of a 'systems approach' to training. The system selected for use by the U.S. Army was Instructional Systems Development (ISD), developed in 1975 by Florida State University. ISD is a comprehensive five-phase process encompassing the entire training/educational environment. Although ISD is a systematic step-by-step approach, it has the flexibility to be used with both individualized and traditional instruction. - Russell Watson, 1981 (Note: Watson used the term Instructional Systems Development, while the term Instructional Systems Design is mostly used today.)

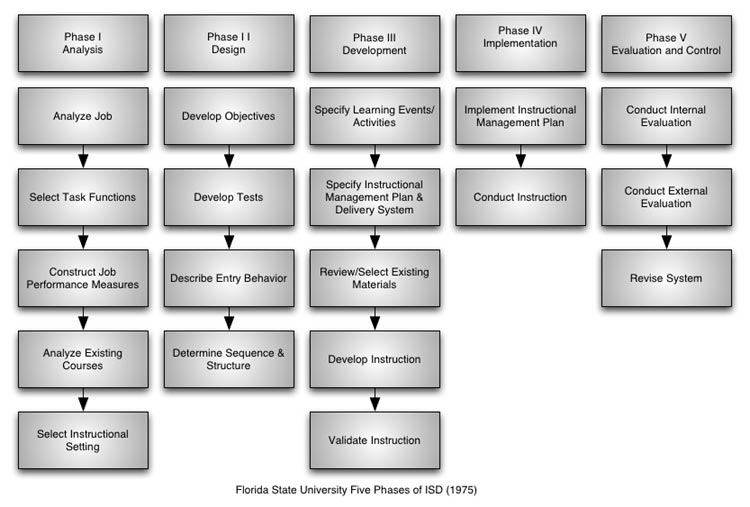

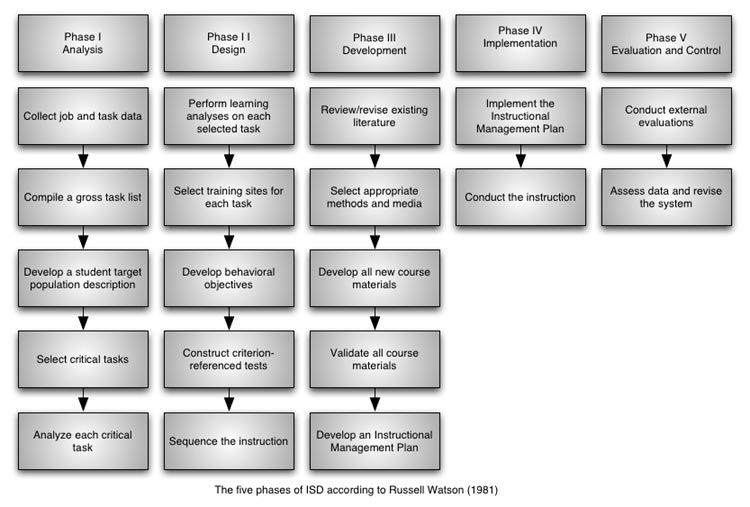

The ADDIE or ISD model consisted of 19 steps that were considered essential to the development of educational and training programs (Hannum, 2005). The steps were grouped into five phases (Analysis, Design, Development, Implement, and Evaluate) to facilitate communication of the ISD model to others. The steps, listed under their respective phases, are shown below:

The military, having a large number of instructional designers and being a leader in training and learning, was a great influence to corporate and educational activities adapting ISD or ADDIE.

Revised ADDIE Model

Six years later, Dr. Russell Watson (1981), Chief, Staff and Faculty Training Division of the Fort Huachuca, Arizona, presented a paper to International Congress for Individualized Instruction. In it, he discusses the ADDIE model as developed by Florida State University. His presentation contained a slightly revised model:

Watson's model was based on the one developed by Florida State University in that the five phases are the same, but the steps within each phase have been slightly modified (Branson, Rayner, Cox, Furman, King, Hannum, 1975).

This site uses a version that differs from the above two versions in that the steps have been changed to more accurately reflect the needs of today's organization. You can learn about it here.

ADDIE Model

A model is a simplified abstract view of a complex reality or concept. Silvern defines a model as a “graphic analog representing a real-life situation either as it is or as it should be” (AECT, 1977). This makes ADDIE a model. While it has been pictured in several ways, the model below shows one popular way (U.S. Army, 2011, p62):

ADDIE has often been called a process model; however, this is only true if you blindly follow it (DeSimone, Werner, Harris, 2002). A much better way to use ADDIE is to think of it as a guide for gaining direct intuitive insight into a problem, for an example see, ADDIE and the 5 Rules of Zen.

ID (Instruction Design) models differ from ISD models in that ISD models have a broad scope and typically divide the instruction design process into five phases (van Merriënboer, 1997). Note that some ISD models, such as the Dick and Carey ISD model, may not use the same terms, but have the same concepts:

-

Design (some models combine it with Development)

-

Development or Production

-

Implementation or Delivery

ID models are less broadly focused in nature, thus they normally go into much more detail, especially in the design portion. ID models are normally employed in conjunction with ISD models as explained in the section, Extending ADDIE.

The Dynamics of ADDIE

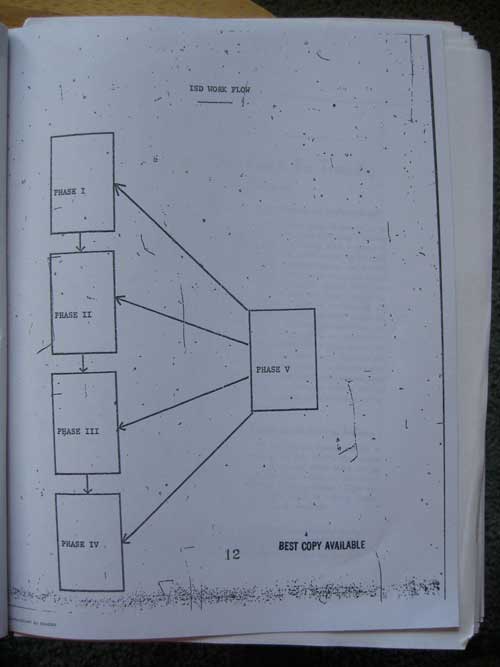

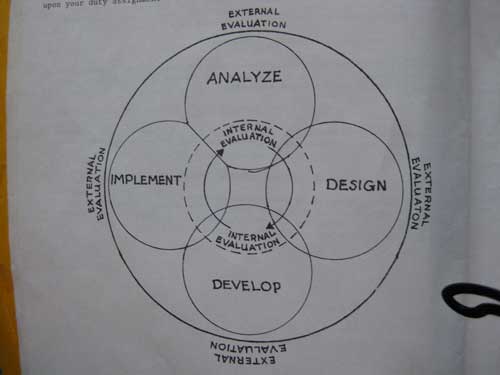

When the ADDIE model first appeared in 1975, it was mostly a linear or waterfall model. For example, in October 1981, Russell Watson presented a paper and wrote:

The five phases of ISD are analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation and control. The first four are sequential in nature, but the evaluation and control phase is a continuous process that is conducted in conjunction with all of the others.

He included this diagram with his paper:

However, it was NOT strictly linear in nature (waterfall) since evaluations were performed throughtout its lifecycle, thus the designers had to iterate to correct any flaws found in the evaluations.

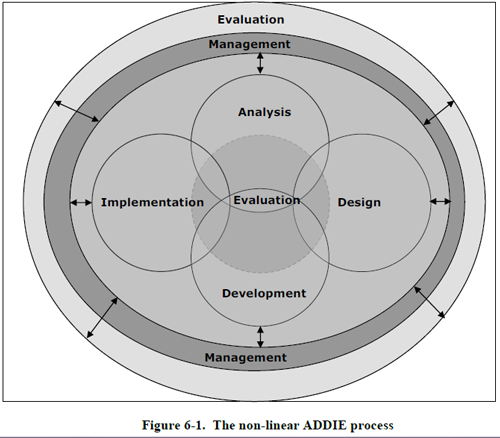

By 1984, the model evolved into a more dynamic nature for the other phases of the model. This was lead by the U.S. Armed Forces. For example, one U.S. Army (1984) training manual reads,

As the model shows, all parts are interrelated. Changes, which occur during one-step of the model, may affect the other four steps. In the ISD process, nothing is done in isolation, nor is all done in a linear fashion; activities of various phases may be accomplished concurrently.

The manual (U.S. Army, 1984) contains the following model that shows its evolving dynamic nature:

The U.S. Army is perhaps one of the most disciplined and structured organizations in the world; however, even they could not design training in a strictly linear manner, thus they evolved ADDIE into a more dynamic nature. Since the original ADDIE model was designed in a university, they took a summative approach in order to evaluate the validity of the learning and training concepts that were used in the learning process.

However, Instructional Designers who work in most organizations are far more concerned with actually producing an effective learning process to meet the needs of the business, thus they take a more formative approach in order to refine goals and evolve strategies (agile design) during the entire ISD process.

In addition, Merriënboer wrote in 1997 (p3):

The phases may be listed in a linear order, but in fact are highly interrelated and typically not performed in a linear but in an iterative and cyclic fashion.

In addition to evolving to a more dynamic structure, the last phase was changed from “Evaluation and Control” to simply “Evaluation” (Hannum, 2005). Thus, the model becomes ADDIE and not ADDIEC.

The Army's newest training manual calls it the “The Non-Linear ADDIE Model” and describes the phases as not sequential (TRADOC Regulation 350-70, 2011, pp61-62).

While the Air Force writes,

“The updated ISD model has been designed to represent simplicity and flexibility so that instructional system developers with varying levels of expertise can understand the model and use it to develop effective, efficient instructional systems. This model depicts the flexibility that instructional developers have to enter or reenter the various stages of the process as necessary” (AF Manual 36-2234, 1993).

ADDIE The Acronym

While the ADDIE model has been around since 1975, it was generally known as SAT (System Approach to Training) or ISD (Instructional System Design). The earliest reference that I have been able to locate that uses the acronym of “ADDIE” is a paper by Michael Schlegel (1995), in A Handbook of Instructional and Training Program Design.

Schlegel writes:

This generic Design Model of Analyze, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation (ADDIE) is utilized, and detailed job aids are provided in the form of rating sheets and checklists..

Other early uses include:

For more information, see ADDIE the Acronym.

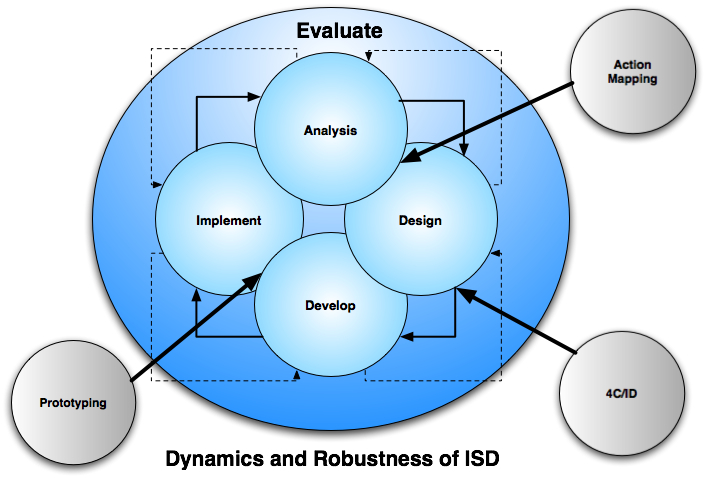

Extending ADDIE

The broad scope and heuristic method of ISD has often been criticized because it tells learning designers what to do, but not how to do it. Yet it is this broad and sketchy nature of ISD that gives it such great versatility. Merriënboer (1997, p3) notes that other ID and learning models can be used in conjunction with ISD.

Thus, ISD becomes a plug and play model — you add other components to it on an as needed basis. For example, the ISD model below has Action Mapping, 4C/ID, and Prototyping plugged into it for designing a robust learning environment for training complex skills:

ADDIE Shortcomings

While ADDIE strives to identify adequate on-the-job performance so that the learners can adequately learn to perform a certain job or task (Branson, Rayner, Cox, Furman, Hannum, 1975), it was never meant to determine if training is the correct answer to a problem. Thus, the first step when presented with a performance problem is to use a performance analysis tool.

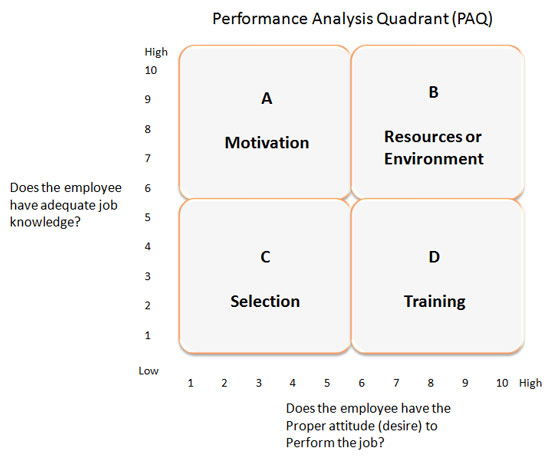

One such tool is the “Performance Analysis Quadrant” (PAQ) for identifying the root causes of such problems. By discovering the answer to two questions, “Does the employee have adequate job knowledge?” and “does the employee have the proper attitude (desire) to perform the job?” and assigning a numerical rating between 1 and 10 for each answer, will place the employee in 1 of 4 performance quadrants:

-

Quadrant A (Motivation): If the employee has sufficient job knowledge but has an improper attitude, this may be classed as a motivational problem. The consequences (reward and punishment) of the person's behavior will have to be adjusted. This is not always bad as the employee just might not realize the consequence of his or her actions.

-

Quadrant B (Resource/Process/Environment): If the employee has both job knowledge and a favorable attitude, but performance is unsatisfactory, then the problem may be out of control of the employee, such as a lack of resources or time, the task needs process improvement, or the workstation is not ergonomically designed.

-

Quadrant C (Selection): If the employee lacks both job knowledge and a favorable attitude, then that person may be improperly placed in the position. This may imply a problem with employee selection or promotion, and suggests that a transfer or discharge be considered.

-

Quadrant D (Training and or Coaching): If the employee desires to perform, but lacks the requisite job knowledge or skills, then some type of learning solution is required, such as training, coaching, or informal learning.

Note: The four quadrants are based on Jones' (1993) description of the four factors that affects job performance.

The ISD model shown below has a:

- performance analysis plugged into the top, left corner,

- ADDIE model (bottom, left),

- ID model (center) to give it further design capabilities, and

- the learning environment or solution (right side), which in turn, helps to create the desired performance (top, right):

Other shortcomings have been leveled at ADDIE, but they seem to be mostly baseless, for example:

-

ADDIE does not lead to the best instructional solutions, nor does it provide solutions in a timely or efficient manner. Reality — This is only true if you do not understand it, use it blindly, or fail to plug in other ID models that best fit the problem and solution.

-

ADDIE doesn't take advantage of digital technologies that allow for less-linear approach, such as rapid prototyping. Reality — As noted above, van Merriënboer, U.S. Air Force, and the U.S. Army point out that it is indeed quite agile and interactive.

-

The ADDIE method is not really the way instructional designers do their work. Reality — ADDIE came about as the Vietnam War was ending, since then the U.S. Armed Forces have been using it quite successfully in a VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity) environment.

-

No original ADDIE model exists. Reality — As this site shows, there is a real ADDIE model.

Next Steps

Next Chapter: ADDIE and the 5 Rules of Zen

Return to the History of Instructional System Design

Additional Resource: ISD Concept Map

References

AECT, (1977). Educational Technology: Definition and glossary of Terms (Vol 1). Washington DD: Association for Educational Communications and Technology. p168

Branson, R.K., Rayner, G.T., Cox, J.L., Furman, J.P., King, F.J., Hannum, W.H. (1975). Interservice procedures for instructional systems development. (Vols. 1-5) TRADOC Pam 350-30, NAVEDTRA 106A. Ft. Monroe, VA: U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command.

Branson, R.K., Rayner, G.T., Cox, J.L., Furman, J.P., King, F.J., Hannum, W.H. (1975). Interservice procedures for instructional systems development: Executive summary and model. (Vols. 1-5) TRADOC Pam 350-30, Ft. Monroe, VA: U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command.

DeSimone, R.L., Werner, J.M., Harris, D M. (2002). Human Resource Development. Orlando, FL: Harcourt, Inc.

Dick, W., and Carey, L. (2014). The Systematic Design of Instruction. Pearson Education, 8th ed.

Gustafson, K., Branch, R.M. (1997). Instructional Design Models. Syracuse, NY: ERIC Clearinghouse on Information and Technology.

Hannum, W.H. (2005). Instructional Systems Development: A thirty year retrospective. Educational Technology, 45(4), 5-21.

Jones, B. (1993). The Four Domains Affecting Job Performance. Moving from Theory to Practice: Integrating Human Factors into an Organization, 1995. Mancuso, V. (ed). Seattle WA: Annual Flight Safety Foundation Conference. Retrieved from http://www.crm-devel.org/ftp/mancuso.pdf

Schlegel, M.J. (1995). A Handbook of Instructional and Training Program Design. ERIC Document Reproduction Service ED383281.

Department of the Air Force (1993). Instructional System Development. AF Manual 36-2234.

Department of the Army (2011). Army Learning Policy and Systems. TRADOC Regulation 350-70.

U.S. Air Force (1970). (Instructional System Development (ISD). AFM 50-2. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Army Field Artillery School (1984). A System Approach To Training. ST - 5K061FD92. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Army (2011). Army Learning Policy and Systems. TRADOC Reg. 350-70. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

van Merriënboer, J.J.G. (1997). Training Complex Cognitive Skills: A Four-Component Instructional Design Model for Technical Training. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Educational Technology Publications.

Watson, R. (October 1981). Instructional System Development. Paper presented to the International Congress for Individualized Instruction. EDRS publication ED 209 239.